China 2030

Green Transition Leader or Carbon Reduction Spoiler?

China’s official goal of peak CO2 emissions by 2030 (versus the EU’s 55% reductions) and complete carbon neutrality by 2060 (versus the EU’s 2050) is seen by some as unattainable if current growth targets and industrial modalities are to be maintained. Indeed, the very design of a key national implementation mechanism, the national Carbon Exchange Trading System (ETS) suffers from some shortcomings when viewed from the point of view of e.g. the EU ETS countries. After a proposal for a national carbon tax was rejected as early as 2013, a pilot phase involving several of the most polluting industries in the worst affected regions was launched. China's first national ETS was launched in 2021, with coverage of the power sector, based on a 'carbon intensity' benchmark, not an absolute emissions cap. Other sectors were scheduled to follow in subsequent years.

In its early phases, only electric generation plants and ‘captive’ industrial power generation facilities serving dedicated industrial sites were included, with other generation sites e.g. natural gas, as well as aviation, ground transport, construction and petrochemicals slated for later entry dates. Moreover, the entire power generation sector only represents an estimate 30% of all carbon emissions in China.

Thus targets could be reached not only by reducing total emissions, but also through a higher growth rate, with the emissions percentage reduced accordingly, such that the higher the achieved growth rate, the greater the absolute pollution level allowed.

In recent years the traded price of carbon emissions in China has remained at a fraction of the EU ETS price, fluctuating at roughly between a quarter and a sixth of the EU compliance regime's price of carbon. As the strain imposed on European industry in the face of cheaper competition persisted, the EU finally adopted plans for a controversial carbon 'border tax', to be implemented in January 2026. (see Events)

Despite this notable departure from accepted norms the Chinese ETS is nevertheless the largest sytem of its kind in the world. Ambitious in its scope and potentially comprehensive in its coverage, if all the key sectors earmarked for inclusion do finally get brought into the system on a true 'cap and trade' basis. In August 2025 Beijing announced a plan to end the 'intensity' approach to controls, with phase out to begin in 2027.

The EU-Emissions Trading Scheme

Each year the EU systematically reduces allocation of EUAs, he supplies of European Union Allowances with the intent of driving up the prices of carbon emission. This strategy bolsters the Commission's commitment to fostering a market environment that encourages sustainable practices and emission reduction strategies. It illustrates Europe's continued support in the market, a remarkable commitment given the context of a land war at the door or Europe, an energy crisis, and sustained inflation.

The EU-ETS carbon pricing mechanism is designed to regulate and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. And it works, at least within its local marketplace. Over the past two decades, it has evolved into a working tool to reduce emissions at scale, operating within an increasingly well-informed and liquid market.

The EU Commission has outlined clear environmental goals for 2030 and 2050. Those include a 55% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from 1990 levels by 2030. Also, it aims for climate neutrality by 2050 - the amount of greenhouse gasses emitted should be minimized, and any tonne of CO2 emitted should be removed or offset. To achieve these climate objectives, carbon prices are going to have to continue to increase. It is only when faced with high emission prices that industries have a clear incentive to lower emissions.

From Development

To Certification

To Trading

Paths to decarbonisation: Offsets or Credits?

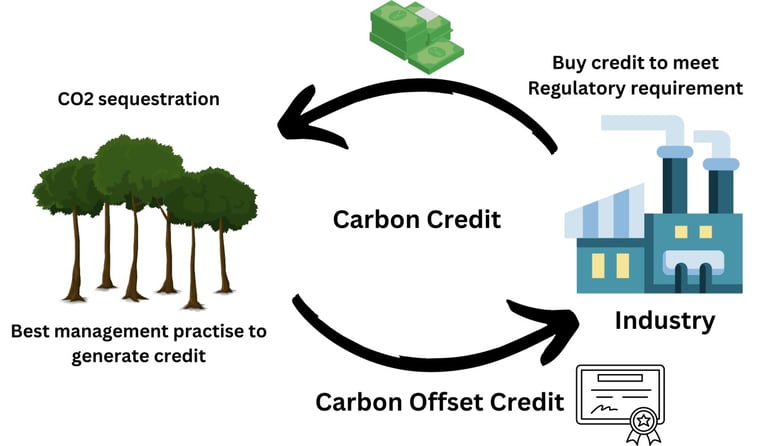

Carbon offsets and carbon credits are closely related concepts in the context of carbon emissions reduction, but they have distinct meanings:

Carbon Offsets

Definition: Carbon offsets are reductions in greenhouse gas emissions (or increases in carbon storage) that can be used to compensate for emissions produced elsewhere. They are typically measured in metric tons of CO2 equivalent.

Function: When a company or individual purchases a carbon offset, they are essentially funding projects (like reforestation, renewable energy, or energy efficiency) that reduce emissions, thereby offsetting their own carbon footprint.

Carbon Credits

Definition: Carbon credits are specific units representing the right to emit one ton of CO2 or its equivalent in other greenhouse gases. They are often created and regulated under cap-and-trade systems.

Function: Companies that reduce their emissions below a certain cap can sell their excess credits to others that exceed their limits. This creates a market for carbon emissions trading.

Regulation: Carbon credits are often part of regulatory frameworks and can be traded in carbon markets, while carbon offsets are generally voluntary and purchased by companies or individuals looking to reduce their impact.

Origin: Carbon credits come from verified emissions reductions tied to regulatory programs, whereas carbon offsets can be generated from a wide variety of projects, which may or may not be verified.

Market Dynamics: Carbon credits are typically subject to market trading and price fluctuations, while carbon offsets are usually sold at a fixed price based on project type and verification.

Key Differences

While both serve to mitigate climate change, carbon credits are more about compliance and regulatory frameworks, while carbon offsets are often voluntary efforts to balance emissions.